Sara Z. Meghdari

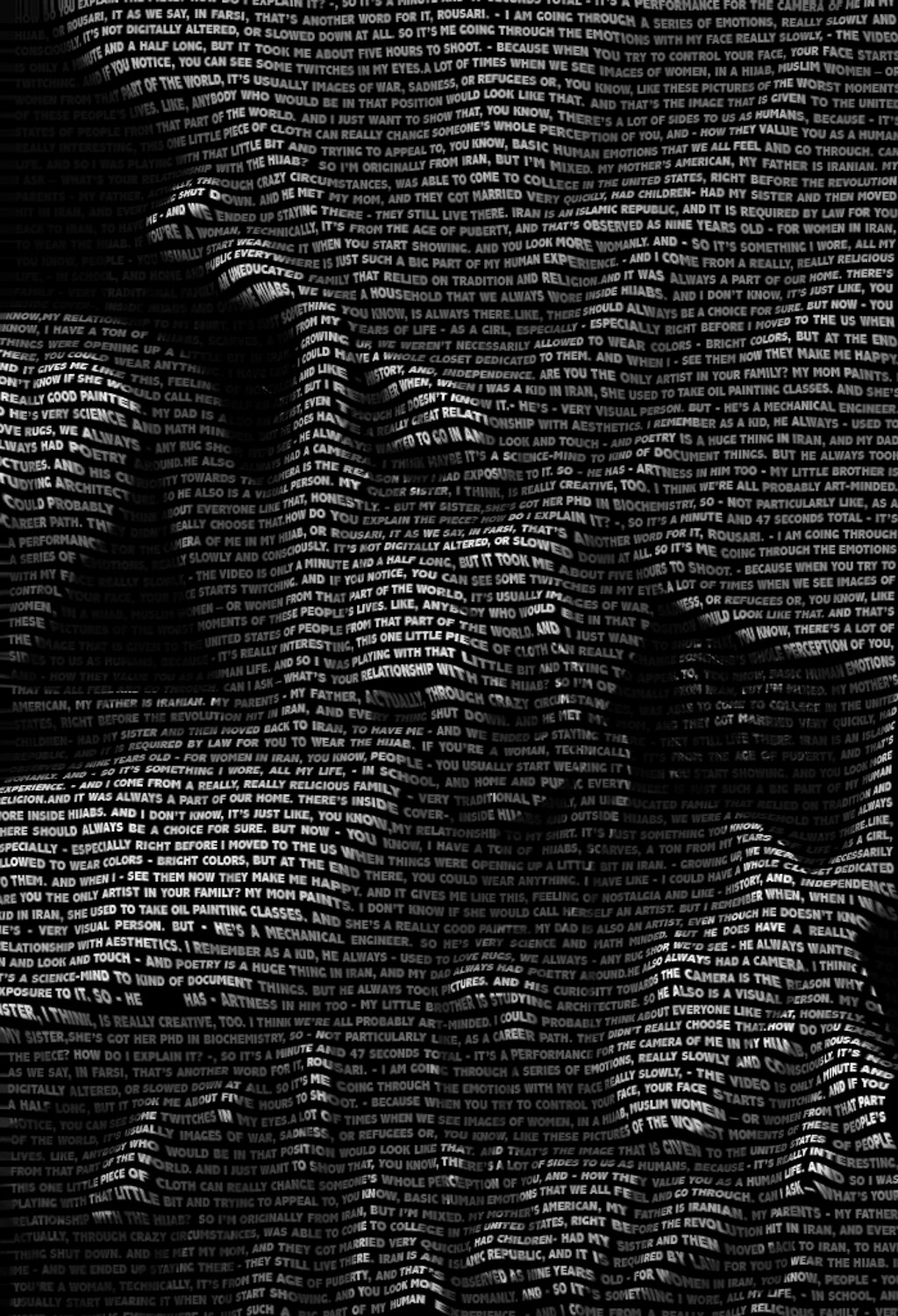

Digital Composite, Brandon Perdomo 2021

Brandon Perdomo

Brooklyn, NY

Interviewer

Sara Meghdari

Brooklyn, NY

Narrator

Session Conducted:

Zoom / Online

2 November 2020

S

We’re in 2020. So it’s quarantine -

COVID.

Election year.

I recently have been trying to keep busy

to hustle and take advantage of this time

and - remind myself to keep going --

B

--, what happens in the studio lately?

S

- When I talk about the studio – it’s not my studio, it’s the studio I work in. There’s a couple photographers that have rented the space out. All of them do major commercial work. And have little personal projects here and there. So when I go there, I’m 100% of the time usually working on somebody else’s work. So it’s like busy work, office work, archiving and things like that.

But it’s nice to -,

go into a different space.

As a photographer, mostly videographer and - lens based - I don’t really need a studio usually unless I’m planning a performance or an installation.

B

- when we met and you had that that piece

projected on the wall, - that piece is typically projected, is that right?

S

- No, not necessarily - originally made to be put on a vertical hanging screen as like a portrait - a moving portrait.

It’s changed in screen sizes and projection sizes. It really - at this point - doesn’t really matter. As long as it’s being seen, but originally it was on it was supposed to be on screen.

B

Can you remind me the name of it?

S

Silent Self

Silent Self, Sara Meghdari

Performance for the camera

2014

B

When - was that put together?

S

- I made that in 2014 actually, when I was in school, it was the first year I was in school. - I got so much shit for making that video. Since then, I talked to a lot of Muslim women artists or women who come from the same background. And they all kind of get the same feedback in these, white - centered schools that - you know, hijab is so overplayed, like, everybody does this, why are you doing this? It’s so overplayed -

It’s going back to the question of identity. It’s like, they really don’t like this portion of our identity. And don’t like to see it. I don’t know. And so when I was in school, I got a lot of that feedback from the Dean of the department, from my critique teacher at the time. But I wanted to make it anyway, so I made it anyway. And I’ve kind of like this great redemption, because it’s one of my works that’s been shown the most.

B

I love that that image of the of the piece being projected on the - wall of a building?

S

Yeah, that was this year. There’s this group called Straight Through the Wall – they’re kind of a guerrilla group of video artists that do this every year. And - it was an open call, I applied - the theme was portrait, so it seemed perfect. I got accepted - and I got to see this video bigger than I’ve ever seen before on a building – in New York city, in America. So it’s kind of intense.

via: Straight Through the Wall

Instagram: @sttw_nyc

B

How do you explain the piece?

S

How do I explain it? -, so it’s a minute and 47 seconds total - it’s a performance for the camera of me in my hijab, or rousari, it as we say, in Farsi, that’s another word for it, rousari. - I am going through a series of emotions, really slowly and consciously. It’s not digitally altered, or slowed down at all. So it’s me going through the emotions with my face really slowly, - the video is only a minute and a half long, but it took me about five hours to shoot. - Because when you try to control your face, your face starts twitching. And if you notice, you can see some twitches in my eyes.

A lot of times when we see images of women, in a hijab, Muslim women – or women from that part of the world, it’s usually images of war, sadness, or refugees or, you know, like these pictures of the worst moments of these people’s lives. Like, Anybody who would be in that position would look like that. And that’s the image that is given to the United States of people from that part of the world. And I just want to show that, you know, there’s a lot of sides to us as humans, because - it’s really interesting, this one little piece of cloth can really change someone’s whole perception of you, and - how they value you as a human life. And so I was playing with that little bit and trying to appeal to, you know, basic human emotions that we all feel and go through.

B

Can I ask – what’s your relationship with the hijab?

S

- So I’m originally from Iran, but I’m mixed. My mother’s American, my father is Iranian. My parents - my father, actually, through crazy circumstances, was able to come to college in the United States, right before the revolution hit in Iran, and everything shut down. And he met my mom, and they got married very quickly, - had my sister and then moved back to Iran, to have me - and we ended up staying there - they still live there.

Iran is an Islamic Republic, and it is required by law for you to wear the hijab. If you’re a woman,

technically,

it’s from the age of puberty, and that’s observed as nine years old for women in Iran, you know, people - you usually start wearing it when you start showing. And you look more womanly. And - so it’s something I wore, all my life, - in school, and home and public - everywhere - it’s just such a big part of my human experience.

- And I come from a really, really religious family - very traditional family, an uneducated family that relied on tradition and religion.

And

it was always a part of our home.

There’s inside cover-, inside hijabs and outside hijabs, we were a household that we always wore inside hijabs. And

I don’t know, it’s just like, you know,

my relationship to my shirt. It’s just something you know, is always there.

There should always be a choice for sure. But now - you know, I have a ton of hijabs, scarves, a ton from my years of life - as a girl, especially -

Especially right before I moved to the US when things were opening up a little bit in Iran. - growing up, we weren’t necessarily allowed to wear colors - bright colors, but at the end there, you could wear anything. I have so many hijabs - I could have a whole closet dedicated to them. And

when I -

see them now they make me happy. And they give me this, feeling of nostalgia and - history, and, independence.

B

Are you the only artist in your family?

S

My mom paints. I don’t know if she would call herself an artist. But I remember when, when I was a kid in Iran, she used to take oil painting classes. And she’s a really good painter. My dad is also an artist, even though he doesn’t know it.

- He’s

- a very visual person.

But -

he’s a mechanical engineer. So he’s very science and math minded. But he does have a really great relationship with aesthetics.

I remember as a kid, he always - used to love rugs, we always - any rug shop, we’d see - he always wanted to go in and look and touch - and poetry is a huge thing in Iran, and my dad always had poetry around.

He also always had a camera. I think maybe it’s a science-mind to kind of document things. But he always took pictures.

And his curiosity towards the camera is the reason why I had exposure to it. So - he has - artness in him too - My little brother is studying architecture. So he also is a visual person. My older sister, I think, is really creative, too. I think we’re all probably art-minded. I could probably think about everyone like that, honestly. - But my sister, she’s got her PhD in biochemistry, so - not particularly like, as a career path. They didn’t really choose that.

S

I definitely feel way way more comfortable in New York City. I was actually having my anxiety - about going back to Colorado because in New York, you never really see Trump supporters - even if you do, they’re not particularly - public about it. But in Colorado, apparently it’s full of them. So - the last time I saw like an - a red hat Trump supporter was in the airport, like two years ago. And an immediate fear went down my heart, like, -

- Oh, my God, can he tell? Can he tell I’m from Iran?

- I don’t know. It was just, this immediate, Oh, hide! - I definitely am feeling a little anxiety, about going back to Colorado, I definitely felt that way, my entire time in Colorado, it was always a matter for me to blend in. Especially when I stuck out so hard and - in the beginning, - and it was not - a fun experience. So my next five years of life was just like, blend in - blend in - blend in. And, you know, don’t attract attention.

And I was very quiet.

I was really observing, I think, - I spent years observing - before I kind of found my voice and my power -

- to speak. And then

when, - New York City,-

you know, [it] is a huge result of that - living here.

and going to school - having to argue with these people.

B

- what really struck me when I really got to sit down and see [Silent Self] as, not just a static image on the wall – at - you know, our friend’s wall in a party. - - it placed me, or invited me - and then placed me in this place of reflection. It’s just -, watch and understand and feel. And I feel - with what I watch and hear from you, - your work tends to do that. And I was thinking about when you were talking about this conversation archive that you were facilitating between people - Can you can you talk about that?

S

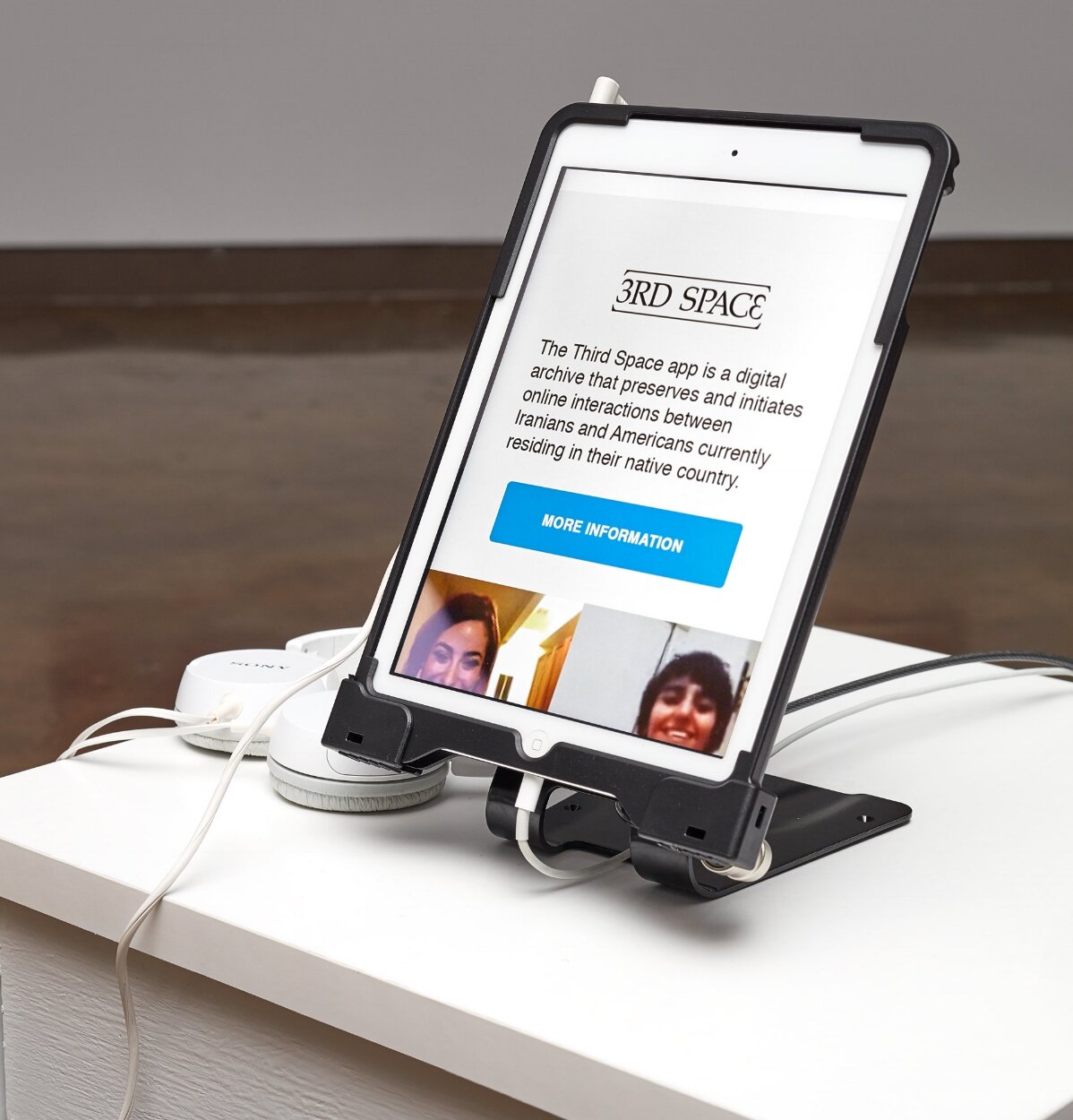

That piece is called 3rd Space. - And it was my thesis project in school. And it ended up being - kind of an archival app of conversations between Iranians living in Iran and Americans living in America. And - - it was kind of an experiment, - it was kind of like, a social experiment.

I don’t know. -

being mixed - being Iranian-American, one of my biggest dreams in life, was for my Iranian family, - extended family to meet my American extended family. How great would it be to have everybody in one space? And that is physically impossible. Not only because of the distance, but because of the politics. And, you know, there’s no way that these people could get a visa either-way, you know, both ways. So I started thinking about, okay, what spaces can I find, for people to share, and the internet obviously, is like one of the only spaces - that – still – kinda - is borderless.

So - that’s where that idea came from. And when I first started, I was experimenting with my friends, like, my high school friends from Iran, with my college friends from the US - having them talk. And it was just such a great, weird conversation of cultures and language, clashing. And I started, you know, experimenting, really, and learning from my experiments and developing like a process and developing, - trying to develop a way that I can get these two people to connect with each other. Like, how can I get in this space that we are?

The 3rd Space App, Sara Meghdari

Installed at the SVA Chelsea Gallery in 2006

How can I get these two people to really see each other -

To really leave this conversation with, like a reflection, and that was really sweet, what you said, Thank you, I think that’s my, that’s the purpose of my work - is to kind of bridge the gap and to bring understanding. That’s where the heart is and where it’s really coming from. And so, 3rd Space allowed me to kind of create like these little incubators of connection.

And it was a lot of work. But it was incredibly rewarding. Every connection was like a new baby being born. That’s how I felt - like I had 50 babies. And some of the people still talk to each other to this day.

So - It was a really great experiment - it kind of lives in this historical space right now, in terms of idea – And one day, I would like to maybe try to reach out and get - the same people to have another conversation maybe like 10 years down the road or something.

But we’ll see.

B

- if you can go back in any time of your - childhood or creative process or voice-finding process. If you could give yourself advice that you wish you had or would like - as a note - is there is there anything?

S

The feeling of hopelessness, does not last - that’s probably what would have been something I would like to have heard when I was younger.

Yeah.

It’s not forever.

So just -

- make it out of it.

just be patient.