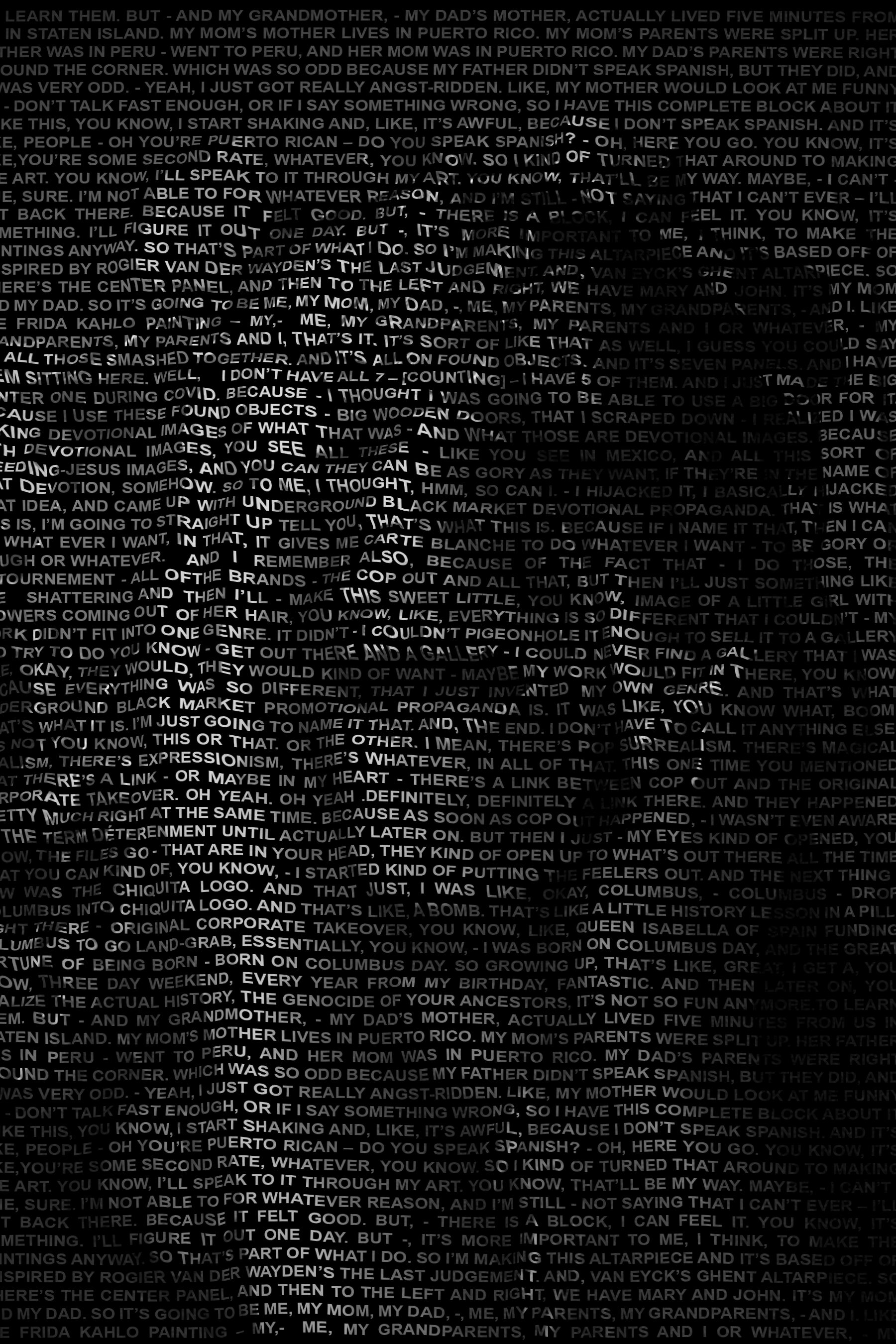

Lazarus Nazario

Digital Composite, Brandon Perdomo 2021

Brandon Perdomo

Brooklyn, NY

Interviewer

Lazarus Nazario

Bronx, NY

Narrator

Session Conducted:

Zoom / Online

23 October 2020

B

- you’re over in the Bronx?

L

I am in the Bronx. I’m in the boogie-down for about a decade now.

B

- can we start out - as much as you’d like - tell me what you’ve been up to these days?

L

Well, yeah, COVID, huh? How about that COVID, man. Yeah, it’s - it’s been rough. It’s been rough, I’m not gonna lie. Um - I live across the street from a hospital. So I got to hear lots of sirens, 24-seven, for a long time.

Um, so that was kind of rough. And I was painting - I was pretty much into like this series of paintings that I was working on, called Great Expectations, which is a series of works where nature takes the earth back.- they are meant to be found photographs from a time when nature took the earth back. So it’s a sort of Future/Past thing.

And - when COVID hit, and I remember, it started to get all infused into the work. I was working on one particular painting called The East River Gardenia Visits the Brooklyn Bridge - and suddenly - the waves just started getting bigger - the water got rougher.

And everything just started to get really overwhelming. Like I could sense - the waves in the painting, sort of turned into this - the big crest of the wave that we were climbing in New York, with COVID, and how - the numbers were climbing and we went into lockdown and all of this stuff - I was in the middle of painting that, as that was happening. So it got to the point where, what was going on around me [came] out through the work. But - it got overwhelming. - the numbers just got staggering. I found myself every morning - like clockwork, putting on Cuomo just to find out what was happening around town and what was going on and what I should do and what have you-

I had to put that painting down-

I had to put it down.

So I went through a bit of a time when - I call it -

- I guess it’s called a block, but it’s where nothing would come out of my hands. That’s kind of the best way I can put it. Like things - nothing will come out of my hands. You know, because that’s physically how it feels for me, you know, it comes out of the ends of my fingertips somehow, - that spills out of my hands.

And I just couldn’t do it. And, - and that was rough. And I kind of had to just let myself go through that - because it’s a global pandemic. And all this stuff’s going on - there’s sirens outside the window, and I kept trying to get my mind off of it. And there were - I’m watching all all these painters that I know that would just kind of go on and paint the same things that they were painting - just kind of goes as normal and, really a lot of - in a lot of ways for a painter, it is kind of normal, because I do sit here all alone in the studio and it really shouldn’t be any different except for the fact that you can’t leave the house, then that became, you know, very, obvious - you couldn’t get out of your head really anyway because you only have your four walls - and you only have what’s going on around you.

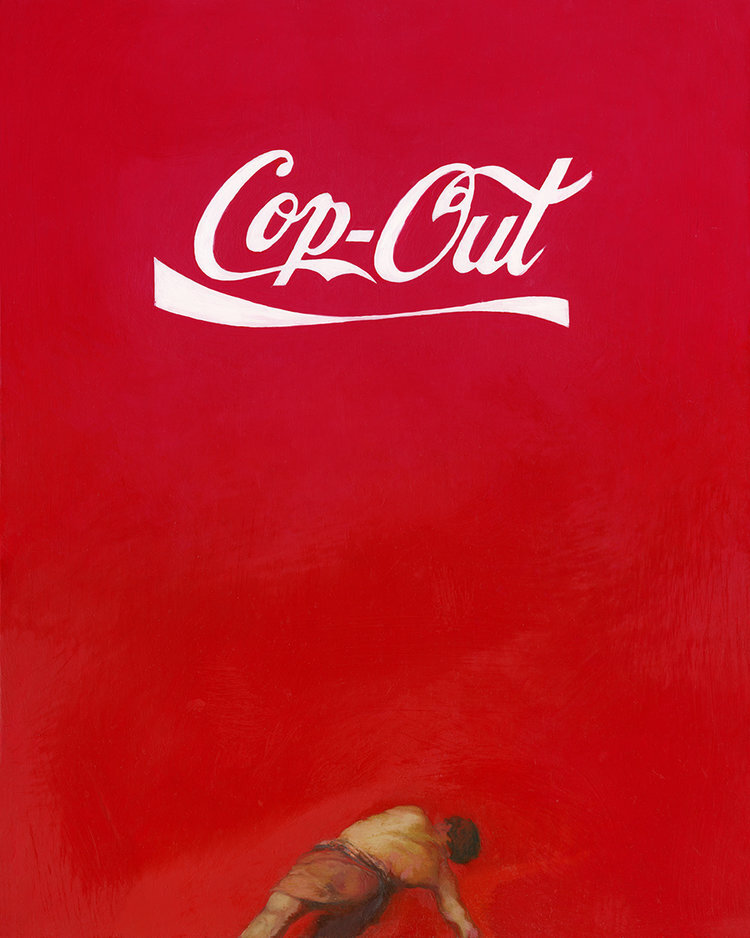

Cop-Out, Lazarus Nazario

16x20 in.

Oil on board

B

Is Cop-Out [a message] that popped in your head?

L

Yeah. Oh, yeah. There’s a whole story for that one. See - backstory. I was on my way to Governor’s Island for the first time that they opened it up, And they had all these spaces that they were opening up to artists, and they were going to give grants and let artists put up shows there. So they were inviting everybody in. And - it was the first time I was going to take the ferry that went there, which is interesting, because I was born in Staten Island. So I’m used to going down there to take that ferry, so I was like, Woah! So weird, I’m going to go to Governors Island. How strange is that?

So I’m walking across the street, and I see a guy heading there.

To the - to that Ferry Terminal carrying these folded up Coca Cola boxes. And to me, you know, - I thought he was one of the artists – it looked like it said, cop out. Wow, that’s awesome. You know, like, that’s so smart. Because that’s exactly what we do. When we give-into advertising. You know, you kind of buy into it, you buy into it, and you cop-out. It’s like, that’s it, you know, you don’t think for yourself, right? Damn, that’s really cool. I wonder what I would do. So I’m walking and walking. And I was like, hmm that’s interesting. And I watched the guy and he’s walking - and he’s walking and he walks back to the Coca Cola truck, and gets in - but he was a delivery guy. It really was Coca Cola boxes. It didn’t cay cop out. I saw a cop out! It just said, you know, it was a Coca Cola box! So right there. And then it was like, DING! - go home - I had to Google it. I had to Google it. Because I was like, there’s no way someone hasn’t done this already. No way someone hasn’t done this already. And I was like, okay, doesn’t look like it. And I went home and made Cop-Out. I like handcrafted the logo because the logo wasn’t available. So it wasn’t like I had a program that - had those fonts or whatever - handcrafted the logo.

B

So you – were a sign painter, right then.

L

Yeah - and threw the guy in, to look as though he was, sort of someone that just threw a rock at this giant lit-up Billboard. Like the idea of like breaking - break that - idea. You know, think for yourself, show up. Don’t just let someone tell you how to think, feel. But yeah, I was a sign painter. Yeah. Existential sign painter, in a way. It was very strange. But - it was really funny because once I made that, everyone and their mother told me I was gonna get sued. Like, You’re gonna get sued, you can’t use that – you’re gonna get a cease and desist order. And the font wasn’t available at the time, but years later, - the font became available. I remember seeing something like BuzzFeed where they’re like, Top five fonts you should start using right now! One of them was Coca Cola. I laughed, like I guess I’m not gonna get in trouble now. Even though - it’s not exact. Like if you really look at the logo. You can see it’s different. But - to me, it was just, like that - that’s just one of those things that just kind of came down - it came to me - it walked down the street right in front of my face, like that’s what it was, completely.

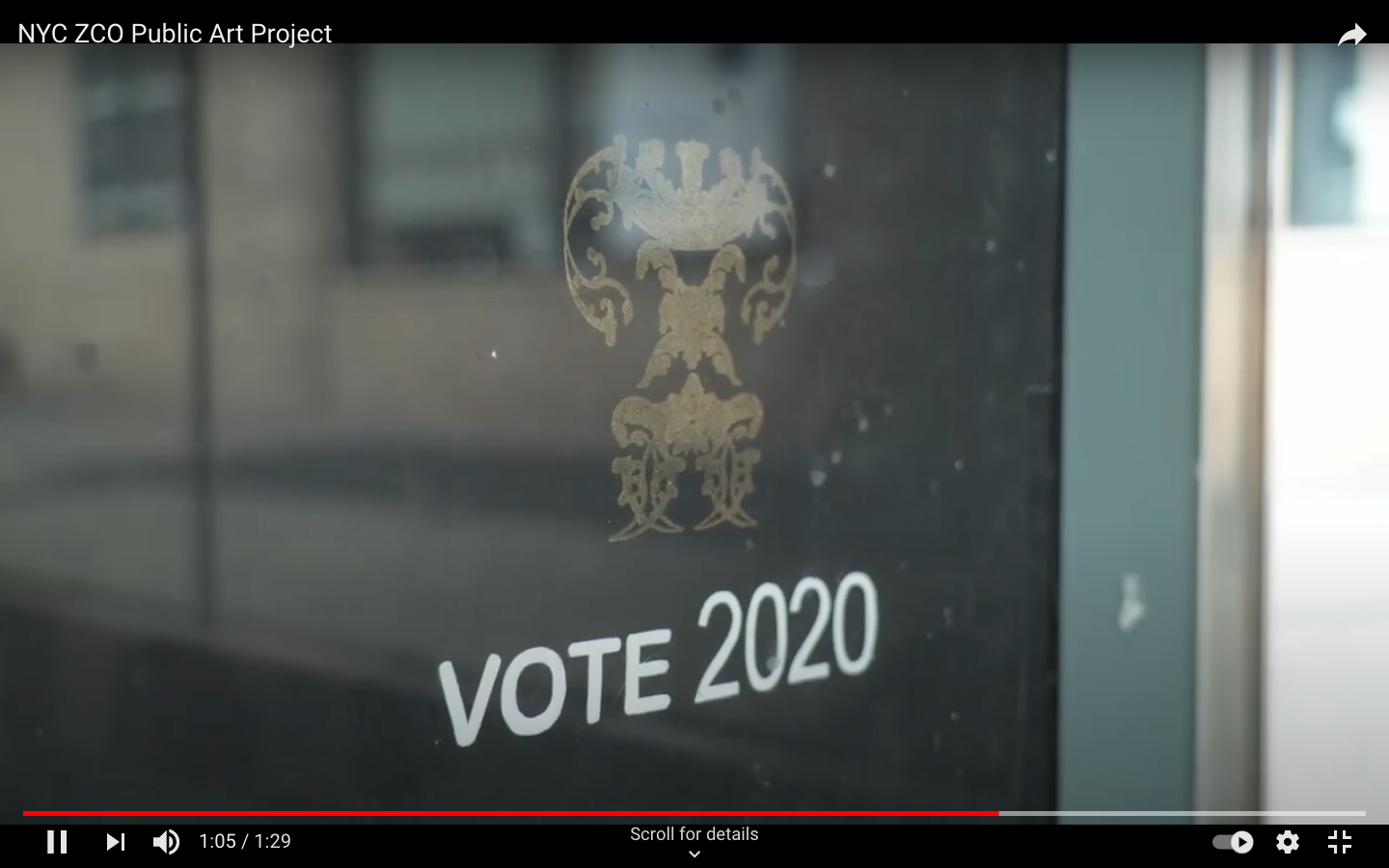

YouTube: NYC ZCO Public Art Project

Five Zero Cop-Out posters were hand painted and installed in all five boroughs of NYC on or nearby the five Black Lives Matter mural streets.

B

And how did Zero Cop-Out come out of that?

L

Zero Cop-Out was born straight from that, which was interesting because the original painting - there is a painting to it. It never got made – it kind of got messed up, and one day, I’ll go back and make it. But it was actually a portrait of Lolita Lebrón, the Puerto Rican nationalist who shot-up Congress over an immigration bill - she brought a gun and shot into the ceiling of Congress over an immigration bill. - It’s an insane story. - and I used zero cop out, and I had this portrait of her - looked like a mug shot. And the background of it was - gold leaf. But you can’t - there aren’t any good pictures of her from then - because it was 1950 -, the pictures are all distorted.

So it was hard to work on it - But that was always in my brain, - there’s no stopping, you know, - You are not going to-not do this. All in, you’re all in, you know, zero cop-out. That’s part of what I call - the détournement pieces, which is - French for hijacking, which is a form of parody, where you take a public service announcement or an ad, and you hijack it for a different meaning - for your own meaning. And even better - an opposite, the opposite to what it says - that’s like, that’s the way to do it.

The sort of rated [rated-] R version of that became Fuck Cop-Out. And I’m actually currently working on what that painting is. Which harkens back to me experiencing racism and an early age. So I’m a painter, and - I’m a big fan of Frida Kahlo. - the way I started painting was that - I actually started out as a singer-songwriter. And I saw this documentary - a point of view about the painter, Leon Golub. And I was blown away. - he’s an existential activist painter. - he died - now, but -

he makes these giant paintings - giant acrylic paintings of like mercenaries and like, you know, just all these big, horrific war-time paintings. And he makes other types of paintings too, but he’s scraping them on the floor with a meat cleaver. Like just - that’s part of his technique. He like sort of paints everything on, scrapes it off, and like, I want to be doing what that guy is doing. I was a singer-songwriter, but I wanted to be doing what he was doing. And I wrote a song for him. Or poem, I guess you could call it, I Pray I feel It Too.

Which is interesting. And it was very, sort of, it kind of foreshadowed that, I guess - I wished I was a painter. And it was the fire in the belly. You know, that was more of what - I pray I feel it too was, like a little prayer - the fire in the belly.

- that same year, I think this was ‘91. That same year, I was reading one of my favorite comics Love and Rockets - by Jaime and Gilbert Hernandez, and they did this little bio on Frida Kahlo. And at the end, it said, taken - you know, such and such story - taken from the biography by - Hayden Herrera - I went straight to the library. Then went to Barnes and Noble and bought that book - Frida Kahlo, The Paintings. And that was it. That was the end of that - I was a painter. I was not a singer-song writer. I was a painter. So I was like this one-two punch of Leon Golub, which is interesting, because it’s this man that paints these gigantic paintings. And this woman that paints these tiny sort of, very personal, very intimate images - but the two kind of smashed together for me, and I came out of that.

L

I was like self taught in acrylics for like 10 years - a good decade before I even was just – gonna, like, - because it took somebody else – Like, go! - pushing me - Okay, all right. Okay, now I can do this, you know, and I did I took to it like a duck out of water and I had a great teacher. Sharon Sprung taught me all about color - and I guess - I mean a colorist. There’s no way around it - like I just can’t - can’t stand it. Color is just too much It’s too gorgeous, and vivid and beautiful, and I have to use all of it and I have to find a way to get it even more vivid sometimes - it’s funny - I look at some of my older work. And - the work I’m doing now looks something like, like one of the peonies girl explosions, - and it’s so much brighter than the earlier flowers I was painting, I was like, No! More! More intense color!

But, it came way later, the whole - all bets are off kind of attitude. And it’s really - a moment where my work changed, and everything changed. And the reason why I worked changed - because I realized I wasn’t gonna have children. That’s it, - guess what, that whole dream, we think, you know, let me wait till I get married. And I got married, and I timed-out, I got married late. And I guess I just didn’t - didn’t have it in me anymore. And I kind of got timed-out by it. So realized that - what I create is all I’m gonna leave - the paintings I create is all I’m gonna leave in this world. - that’s my legacy. I don’t have - a child or something to leave something to, that will, remember me by bla bla bla bla bla, like, a lot of people have. And, you know, some people don’t want that. But I did, I really did. So the moment that happened, - when that all bets are off moment.

That’s kind of when I realized, okay,

I curate everything I do,

because I know it’s gonna be around when I’m gone.

So I’m very aware of that. And I’m very aware of my place in time. And history. And my moment. That’s why also, - I’ve sort of, sort of reclaimed my ethnicity, which I shunned when I was younger because of the racism. And I never, - it was never an easy fit, because I am not Puerto Rican enough for Puerto Ricans. And I’m not white enough for white people - there’s always, you know, I don’t fit in either world. So I never really felt right. And much like Frida did for Mexican painting, I wanted to kind of espouse my, you know, Puerto Rican ethnicity in my work. So I would - I started going to the library on 42nd Street, right, that - big giant library where all the art books are. And just - would come home - I was living in Staten Island at the time, and I would just take out all these giant books and go across the street to the express bus and like, pretty much sit them on the seat next to me - a pile of books almost as big as me, and just pour over them. It was interesting, because I sought out - what, what is Puerto Rican art? I wanted to know really deeply what it was. And I - aside from sort of, say, the, - folk tradition of the kind of Indian Taíno, - kind of art experience, I couldn’t find the contemporary version, - couldn’t find it, like a cohesive, you know, contemporary version. And I just put all the books down, and decided that what I make is - it is because I am - you know, and if I make something that speaks to that, then that is, Puerto Rican art.

So I started to make works - almost like history paintings - in the same way as Frida and Diego – I kind of - take on all these little things, you know, you kind of take on the things that are around you.

Like you put it on, like a sweater and a coat and you kind of see how it fits. So I would grab - I started reading up on Puerto Rican history and pulling stories out of that, - and I’m making works that speak to that.

The biggest one that I’m doing that speaks to that, for me, is an altarpiece which also speaks to my ancestry. And this is something that has been in my brain for about 20 years. But it’s an altarpiece called Birth of a Nuyorican: All The Stigma, None of the Romance - because that’s how it felt to me - - it’s always felt to me, I’ve always had that stigma of being Puerto Rican without the - you know, all that romance being Puerto Rican - of - the dancing, the language, I would try to speak Spanish - I’ve spoken Spanish fluently, not fluently, but like I was trying real hard, getting in there. In Guatemala. For six weeks, I went to Guatemala to learn Spanish. But they speak it very slow there. – they do not speak it like Puerto Ricans - very .. slow .. - and everybody’s very relaxed – it was Antigua, Guatemala - - I have sort of a like brain block with it. Because - my family -my mother spoke Spanish. My father did not - it was not spoken at home - when I was little, my mother would try to teach me words and I would try to learn them. But - and my grandmother, - my dad’s mother, actually lived five minutes from us in Staten Island. My mom’s mother lived in Puerto Rico. My mom’s parents were split up. Her father was in Peru - went to Peru, and her mom was in Puerto Rico. My dad’s parents were right around the corner. Which was so odd because my father didn’t speak Spanish, but they did - it was very odd.

- yeah, I just got really angst-ridden. Like, my mother would look at me funny if I - don’t talk fast enough, or if I say something wrong, so I have this complete block about it - like this, you know, I start shaking and, like, it’s awful, because I don’t speak Spanish. And it’s like, people - Oh you’re Puerto Rican – do you speak Spanish? - Oh, there you go. You know, it’s like, you’re some second rate, whatever, you know. So I kind of turned that around to making the art. You know, I’ll speak to it through my art. You know, that’ll be my way. Maybe, - I can’t - fine, Sure. I’m not able to for whatever reason, and I’m still - not saying that I can’t ever – I’ll get back there. Because it felt good.

But, - there is a block, I can feel it. You know, it’s something. I’ll figure it out one day. But -, it’s more important to me, I think, to make the paintings anyway. So that’s part of what I do. So I’m making this altarpiece and it’s based off of - inspired by Rogier Van Der Wayden’s The Last Judgement. And, Van Eyck’s Ghent altarpiece. So - there’s the center panel, and then to the left and right, we have Mary and John. It’s my mom and my dad. So it’s going to be me, my mom, my dad, -, me, my parents, my grandparents, - and I. Like the Frida Kahlo painting – my,- Me, my grandparents, my parents and I or whatever, - My Grandparents, My Parents and I, that’s it. It’s sort of like that as well, I guess you could say it’s all those smashed together. And it’s all on found objects. And it’s seven panels. And I have them sitting here. Well, I don’t have all 7 – [counting] – I have 5 of them. And I just made the big center one during COVID. Because - I thought I was going to be able to use a big door for it. Because I use these found objects - big wooden doors, that I scraped down -

I realized I was making devotional images of what that was - and what those are devotional images. Because with devotional images, you see all these - like you see in Mexico, and all these sort of bleeding-Jesus images, and you can they can be as gory as they want, if they’re in the name of that devotion, somehow. So to me, I thought, hmm, so can I. - I hijacked it, I basically hijacked that idea, and came up with Underground Black Market Devotional Propaganda. That is what this is, I’m going to straight up tell you, that’s what this is. Because if I name it that, then I can do whatever I want in that, it gives me carte blanche to do whatever I want - to be gory or rough or whatever.

And I remember also, because of the fact that - I do those, the détournement - of the brands - the cop out and all that, but then I’ll just something like The Shattering and then I’ll - make this sweet little, you know, image of a little girl with flowers coming out of her hair, you know, like, everything is so different that I couldn’t - my work didn’t fit into one genre. It didn’t - I couldn’t pigeonhole it enough to sell it to a gallery - to try to do you know - get out there and a gallery - I could never find a gallery that I was like, okay, they would, they would kind of want - maybe my work would fit in there, you know, because everything was so different, that I just invented my own genre. And that’s what underground black market devotional propaganda is. It was like, You know what, boom, that’s what it is. I’m just going to name it that. And, the end. I don’t have to call it anything else. It’s not you know, this or that. Or the other. I mean, there’s Pop surrealism. There’s magical realism, there’s expressionism, there’s whatever, in all of that.

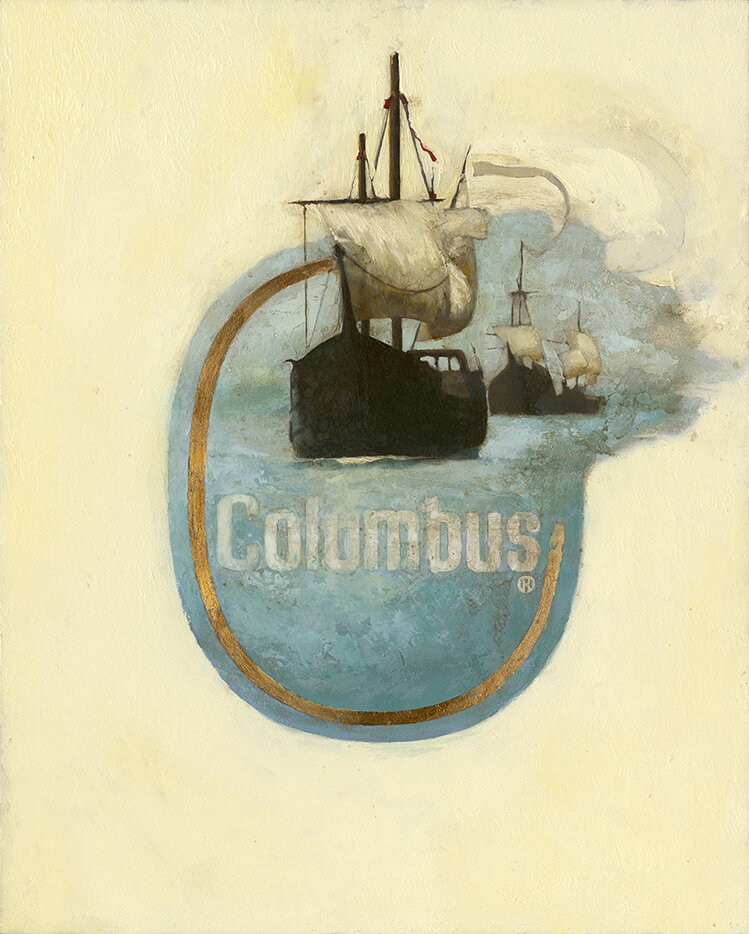

The Original Corporate Takeover, Lazarus Nazario

16x20 in

Oil & gold leaf on board

B

This one time you mentioned that there’s a link - or maybe in my heart - there’s a link between Cop Out and The Original Corporate Takeover.

L

Oh yeah. Oh yeah. Definitely, definitely a link there. And they happened pretty much right at the same time. Because as soon as Cop Out happened, - I wasn’t even aware of the term déterenment until actually later on. But then I just - my eyes kind of opened, you know, the files go - that are in your head, they kind of open up to what’s out there all the time that you can kind of, you know, - I started kind of putting the feelers out. And the next thing I saw was the Chiquita logo.

And that just, I was like, okay,

Columbus, - Columbus - drop Columbus into that Chiquita logo. And that’s like, a bomb. That’s like a little history lesson in a pill. Right there - original corporate takeover, you know, like, Queen Isabella of Spain funding Columbus to go land-grab, essentially, you know, - I was born on Columbus Day, and the great fortune of being born - born on Columbus Day. So growing up, that’s like, great, I get a, you know, three day weekend, every year from my birthday, fantastic. And then later on, you realize the actual history,

The genocide of your ancestors, it’s not so fun anymore.

And it - with imperialism, kind of got wrapped up in that.

And that, that - that’s another one that came to me, then I had to Google. I had to kind of like, look around like, nobody put this together? I remember how I googled it. But I remember thinking that that’s because there’s just - some of those, sometimes things just hit you like that. That one came to me. Because in your mind, you’re thinking how you’re going to put it together. And it isn’t until you see something out in the world, that it can express itself fully - in a concise manner. And it happens rarely - doesn’t happen often. And I remember thinking - I remember trying to keep my eyes open wide during this covid thing, but - I’m too much in this room, even though you can go online and all that, it’s not - it’s not the same. It’s been hard.

But - that felt really good to make. Actually, that’s another one of those that - there’s a couple paintings that I made. Probably corporate takeover, cop out, screen grab and shattering. - if I die tomorrow, I’m okay. I’m okay, that those - those are out in the world, and I’m pretty sure they’re going to be out in the world for a long time. You know, - -, because they do move you - they move you to think or feel. Or, even if you don’t like it, - I had the experience --

I was in one of the Staten Island shows where you kind of had to watch one of the - I don’t know what - it was - - one of the big art shows they do every year.

Art By The Ferry - they asked you to come sit in a room for a while - to watch stuff. And I had The Shattering in there, I was like, This is gonna be awesome. I got to be a fly on the wall. Because people didn’t know that I was the painter that painted it - got to be a fly on the wall. I watched people walk by and react to that one. That was a very interesting thing.

B

- What kinds of people. What kind of reactions?

L

Ah, some of them were like, That’s disgusting. That’s disgusting. Why would you do that - other people - were moved by it deeply. You know, like, ran the gamut - ran the gamut. And I’m like, I’m okay with all of it. I don’t even care. Like my own mom said it looked like somebody vomited while I was packing it up to put in a show because Morley Safer chose it to be in a show called In The News at the Pen and Brush gallery in New York - packing it up. My mom was like - That looks like somebody threw up. Okay. Well, look, it was good enough for Morley Safer, so I don’t mind. You can think that.

B

- Thanks, mom.

L

Yeah, I was like, I get it - -

I mean, I did – I threw it up, really –

it came the heck up, out of me.

The Shattering, Lazarus Nazario

24 x 48 in.

Encaustic, oil and ground glass on board